Nylon: a miniature dataflow engine in Rust

- [redacted] <[redacted]@cmu.edu>

- [redacted] <[redacted]@andrew.cmu.edu>

View this document on the web at https://dayli.ly/15418-project.

This is the final report for our 15-418 course project. Our project is nylon, a pedagogical implementation of a miniature dataflow engine in Rust. The name nylon was chosen because our project shares some similarities with the prevalent Rust parallel programming library, rayon.

Overview

nylon’s architecture has three layers:

- The bottom layer is a work-stealing scheduler;

- The middle layer is a suite of generic data-parallel algorithms;

- The top layer is a dataflow programming engine.

Each layer builds on top of the previous one, and finally the user interacts with the framework via the top layer — the dataflow engine.

This report is structured as follows:

- We first describe

nylon’s API and programming model. - Then, we describe and discuss each of the three implementation layers in detail. We follow the order of: scheduler, dataflow engine, and finally data-parallel algorithms, since it is roughly the same order in which we implemented them. This makes some design decisions easier to motivate.

- Finally, we provide benchmarks on

nylon’s parallel speedup on some synthetic and real-world tasks, as well as some brief discussion of the performance.

What we didn’t implementIn an ideal world, we would like our project to be as feature-complete as possible. In reality, our time is limited. Throughout the report, we describe what we would have liked to implement, but didn’t have time to, in infoboxes like this.

SourceIf you see this infobox, it would point to corresponding source code of the subject being discussed.

API and programming model

Source

src/plan/mod.rs

nylon provides a high-level interface for the user to do dataflow programming, or more broadly declarative data-parallel programming. We provide a plan interface that allows the construction of dataflow DAGs (code is simplified pseudo-Rust):

trait Plan<T> {

fn from(source: Arc<Vec<T>>)

-> Arc<Plan<T>>;

// Apply a transformation to each element of the collection

fn then_map<U>(self: Arc<Self>, transform: Fn(&T) -> U)

-> Arc<Plan<U>>;

// Filter elements of the collection by a predicate

fn then_filter(self: Arc<Self>, predicate: Fn(&T) -> bool)

-> Arc<Plan<T>>;

// Combine values of the same key with a user-supplied function

fn then_reduce_by_key<K, V>(self: Arc<Self>, combine: Fn(&V, &V) -> V)

-> Arc<Plan<(K, V)>> where Self: Plan<(K, V)>;

// Group values of the same key into sub-collections

fn then_group_by_key<K, V>(self: Arc<Self>)

-> Arc<Plan<(K, Vec<V>)>> where Self: Plan<(K, V)>;

// Perform an inner join over two collections

fn then_inner_join<K, U, V>(self: Arc<Self>, other: Arc<Plan<(K, V)>>)

-> Arc<Plan<(K, (U, V))>> where Self: Plan<(K, U)>;

// Left, right, and full outer joins also exist

// Sort values by a given compare functions

fn then_sort_by(self: Arc<Self>, cmp: Fn(&T, &T) -> Ordering)

-> Arc<Plan<T>>;

// A sort-by-key variant also exists

}The user can then construct a plan and run it:

let plan = Plan::from(vec)

.then_map(...)

.then_filter(...)

.then_reduce_by_key(...)

.then_sort_by(...);

let result = plan.execute();nylon’s dataflow engine will traverse the graph and delegate tasks to various generic data-parallel algorithms we implemented. This interface enables very concise programs that are nevertheless efficiently parallelized, allowing the user to focus on high-level transformation structure instead of algorithm implementation details.

Work-stealing scheduler

The most straightforward way to implement parallel algorithms is to divide the work up statically and assign each chunk of work to a fixed thread. This has the advantage of being very simple; however, it often introduces work imbalance. Oftentimes, it is impractical to cheaply divide a task into chunks of equal workload; in this case, some threads may take disproportionately longer to finish work on their own chunk, forcing other threads to wait for its completion in idle.

As such, dynamic work division is needed. This involves dividing work up into more chunks than there are threads, and then have each thread dynamically grab new work. A work-stealing scheduler implements a form of dynamic work division. Core to it are local work queues associated with each worker thread; when one worker thread runs out of work to do, it checks the work queues of other threads and steals a unit of work, achieving load balancing.

The decentralized nature of local work queues greatly reduces contention commonly associated with a centralized global work queue, which is the other common scheme of dynamic work division. In work-stealing, on the “happy path,” where each worker’s workload are roughly equal, little to no stealing needs to occur at all. As a result, each worker mostly accesses their own work queue, free of cache and lock contention.

Interface

Source

src/worker/coordinator.rs

The most fundamental part of nylon is a work-stealing scheduler implemented with the crossbeam-deque Chase-Lev queue. Relevant code can be found in the worker module. This scheduler provides three parallel programming primitives backed by a thread pool, which we use later to build our parallel algorithms:

join(F, G)runsFandGpotentially in parallel (when there is capacity), and returns both their results.scatter(F...)takes an array of tasks, sends one task to each worker to run in parallel, and returns all their results.broadcast(F)sends the same task to all worker threads to run in parallel, and returns all their results.

Note that all these primitives are synchronous: they only return after the tasks they created are done.

join(F, G) naturally enables tree decomposition of parallel tasks, in which tasks are recursively divided into halves and parallelized over, via the following program structure:

fn par_algorithm(input) {

if input.size() < GRANULARITY {

seq_algorithm(input)

} else {

let (left_in, right_in) = input.split_mid();

let (left_out, right_out) = join(

|| par_algorithm(left_in),

|| par_algorithm(right_in),

)

combine(left_out, right_out)

}

}join(F, G) is also the only primitive that introduces stealable tasks. It is implemented as the following steps:

- Put

Gon the local task queue. - Perform

Fon the current worker thread. - If

Gis still on the local task queue, perform it. Otherwise, yield, and potentially sleep, until the completion ofG.

We elaborate on the meaning of the yield operation in the next section.

scatter(F...) and broadcast(F) are, by contrast, convenient tools to implement static work division when workload imbalance is less of a concern. These primitives directly “pin” tasks to threads, which makes these tasks non-stealable. This is achieved by attaching a separate broadcast queue with each worker, which are not eligible for stealing.

We describe how broadcast(F) is implemented, and scatter(F...) is analogous:

- Push

Fonto the broadcast queues of other workers. - Perform

Fon the current worker thread. - Yield, and potentially sleep, until all threads finished performing

F.

Yielding

Source

src/worker/worker.rs

When a worker thread performs join(F, G), logically, it performs F and then “waits” on the completion of G. Similarly, when a worker thread invokes broadcast(F), after it completes the local copy of F, it “waits” on the completion of all other threads.

However, if we make the thread literally wait, e.g. by waiting on a condition variable until a condition has become true, then that thread would be idle when it could be stealing work from other threads and sharing the load. This is highly wasteful of compute resources. Therefore, what they actually do is yielding: namely, trying to contribute to progress by doing other tasks (and potentially stealing from other workers) in the meanwhile.

The yield operation (as defined in Worker::yield_once()) involves these steps:

- If there is work on the local work queue, perform it.

- Otherwise, if there is work on the local broadcast queue, perform it.

- Otherwise, try to steal work from other workers.

- If that also fails, spin for some cycles.

This allows worker threads to be well-utilized even when they are waiting on some other operation’s completion.

Prioritization between broadcasted tasks and stealing tasksOur yield operation prioritizes broadcasted tasks over stealing tasks. In workloads with many broadcasts, this could mean that broadcasts hog workers and operations that depend on work-stealing (

join()) suffers.Another valid design choice is to prioritize stealing first, which may increase

broadcast()latency but ensure work-stealing always remains effective. If we had more time, we would have liked to explore the performance implications by implementing both and benchmarking their behavior in different workloads.

Sleeping and waking

Source

src/worker/sleep.rs

Yielding is useful for keeping workers utilized. However, when there is truly not much work to do, they will be spinning indefinitely. This is undesirable since they still hog CPU resources, which could have been used by other processes to do meaningful work instead.

Therefore, when a worker fails to find any work after a set number of yields, it sleeps until it is waken by another thread. As the particulars of thread sleeping is not a focus of this project, we pulled in an existing implementation, crossbeam_utils::Parker, to enable sleeping and waking. This abstraction is particularly useful in that it allows asynchronous waking: when thread A attempts to wake thread B when it is not asleep, thread B will be waken immediately when it tries to fall asleep the next time. This eliminates a class of race conditions at the cost of potential spurious wakeups, which is a worthwhile tradeoff for our project.

Deciding when to wake a thread involves some subtleties. Any task inside the scheduler is associated with its originating thread and an atomic completion flag, so if the task is stolen, the stealer knows to wake the originator when it completes the task. However, this is not the only scenario where waking is necessary.

Waking workers to do new work

When a worker thread sees no work is available and goes to sleep, more work may arrive shortly after. If it keeps sleeping, then this results in underutilization. In the worst case, all workers might fall asleep, which prevents progress altogether.

Therefore, when a unit of new work arrives via join(), a thread needs to be waken (if there is any sleeping). Similarly, when broadcast() and scatter() is called, all threads need to be waken. Waking all threads is easy to implement; the case for join() is harder. We need to wake at least one thread, but also do so more efficiently than waking all threads.

The naive way to implement this is to try waking threads one by one, until we encounter a thread that was indeed previously sleeping. When all threads are busy, this method is highly ineffective, because virtually any new work would need to attempt to wake all threads, which involves expensive atomic swaps.

Our approach was to introduce a global atomic counter of sleeping threads. Before a thread goes to sleep, it increments the sleep counter; after it wakes up, it decrements the counter. This way, after a thread introduces new work, it can check the sleep counter first, and if it sees no threads are sleeping, it skips the waking step altogether.

This conceptually straightforward idea turned out to be subtle to implement. We encountered a variant of the lost wakeups problem, as illustrated in this series of events:

- Worker A yielded repeatedly and found no work. It decides to sleep.

- A new unit of work is introduced. The originator checks the sleep counter, which reads 0, so it skips the waking step.

- Worker A increments the sleep counter.

Worker A should have been waken to do work, but it wasn’t. In order to solve this problem, we made the worker check for work one last time after they incremented the sleep counter and before they fall asleep; any work introduced before the increment would be detected, and any work introduced after the increment would necessarily see the non-zero counter value and wake the worker.

Randomness in stealing and waking

Initially, when we wrote the scheduler, workers stole work by checking work queues of other workers starting from index 0. Similarly, when they introduced new work and needed to wake a worker, they started checking for sleep states from index 0. This turned out to be highly problematic: due to the deterministic skew this introduces, it often resulted in a small number of workers doing the bulk of the work.

Therefore, we introduced randomness in stealing and waking. When workers attempt to steal work or wake other workers to do work, they randomly chose a starting index and traverses workers circularly until they find a victim. This was effective in distributing the load evenly to all workers.

On-stack task execution

Source

src/worker/job.rs

One consequence of the fully synchronous programming model of our scheduler is that it enables fully on-stack task execution. Since all tasks will be waited on, the surrounding stack frame of any task necessarily lives at least as long as the task itself. Therefore, the task itself can be stored in that stack frame, instead of requiring expensive heap allocation.

To implement this, the main thing to wrestle with is Rust’s concurrency safety mechanisms. Rust prohibits sending references to stack objects across thread boundaries, since it has no way of statically ensuring the reference will not outlive the object itself. As a result, raw pointer manipulation and unsafe code (which allows dereferencing raw pointers) was needed, although they are typically frowned upon in Rust.

Additionally, stack unwinds are also a concern. For example, when join(F, G) is called with F and G on stack, but F panics, then the resulting stack unwinding will cause the entire stack frame to be removed, including the G inside, resulting in undefined behavior when G is next accessed. We used Rust’s std::panic::catch_unwind() function to catch any stack unwinds in task execution and only propagate them when all tasks spawned by a primitive are complete.

Asynchronous parallel primitivesFrameworks like

rayonimplement both synchronous primitives like ours and asynchronous primitives (e.g.rayon::spawn()spawns a task into a worker and immediately returns). If we had more time, we would have liked to implement these asynchronous primitives.These primitives also do not possess the synchronous properties we rely on for on-stack task execution, hence these tasks must be allocated on the heap. This would introduce heterogeneity into our task representation, which we think would be interesting.

Dataflow engine

On a high level, a dataflow engine enables the user to describe a data-parallel program as a DAG of high-level operations like map and reduce, and then carries out that plan efficiently.

This description is vague enough to capture a wide range of software with very different scales and priorities, so we refine the description for our project: nylon’s dataflow engine is single-node, in-memory, and bulk-synchronous.

- Single-node means that we only concern ourselves with computation on one machine, as opposed to a distributed system.

- In-memory means that we do not concern ourselves with larger-than-memory datasets and disk I/O.

- Bulk-synchronous means that the engine operates on pre-specified datasets in bulk as opposed to streaming indefinitely long data streams, and as a result concerns itself more with throughput than latency.

Core implementation

Source

src/lib.rs

nylon’s dataflow engine uses the following execution model that resembles classical bulk-synchronous systems like Spark:

- Find all nodes with no pending upstreams (their upstreams have all finished executing).

- Execute all these nodes in parallel (implemented with

join()in the form of trivial tree decomposition). - When they all finished executing, decrement the in-degrees of their downstreams.

- Go back to step 1.

This execution model naturally enables proper data-sharing. We associate each node with an immutable buffer, where they materialize their output data to. Data in this buffer can then be safely shared across its downstreams in parallel, since none of them will be able to mutate it. This means we never need to execute the same node twice for the result to be available to multiple downstreams.

Sources of parallelism

When implementing a dataflow engine, there are two axes of parallelism that need to be considered:

- Task parallelism refers to executing multiple independent tasks (nodes in the DAG) in parallel.

- Pipeline parallelism refers to executing upstream and downstream tasks in parallel, with the downstream making progress as it gradually receives data from the upstream, instead of waiting for the upstream to finish producing all data.

Task parallelism is useful when a DAG contains nodes with small workloads that cannot saturate the processing power. Executing these nodes with other potentially heavier nodes helps with resource utilization. It is also relatively easy to achieve; in fact, it is trivial in nylon, as we described in step 2 of its execution model:

- Execute all these nodes in parallel (implemented with

join()in the form of trivial tree decomposition).

Pipeline parallelism is more difficult. Fully general pipeline parallelism, where any node is capable of making progress as soon as it receives data from its upstream, is very difficult to implement efficiently, and naive implementations of such schemes can hurt throughput greatly. The main advantage to gain from pipeline parallelism is the reduced latency that comes with streaming. Since our project’s scope is bulk-synchronous processing, we decided against pursuing true pipeline parallelism.

Operator fusion

Source

src/plan/mod.rs

A closely related concept to pipeline parallelism is operator fusion. This refers to finding opportunities within the DAG to combine, or fuse, two nodes into one computationally equivalent node. Operator fusion can selectively remove node boundaries and the associated orchestration and materialization costs, which in turn increases execution speed. We implemented a framework for operator fusion in nylon which we describe below. Conceptually, each node in nylon has a representation like this:

// A DAG node representing a map operation: apply a transformation to each

// element of the collection.

struct Map<T, U, Upstream: Plan<T>> {

// The per-element transformation

map_fn: Fn(&T) -> U

// ^^ This is not proper Rust, but we simplify it here for

// presentational purposes

// The upstream node

upstream: Arc<Upstream>

// ^^^ Arc is Rust's ref-counting smart pointer

}Which is to say, each node points to its upstream dependencies. Consequently, a data pipeline is in fact the same as the last node (the “output node”) in that pipeline, which points to its upstreams, which then point to their respective upstreams, forming the entire pipeline.

Then, it is straightforward to see how operator fusion could be implemented: we could define pipeline construction methods like .then_map() and .then_filter() in a trait (similar to an interface in other programming languages). Then on each node type, these methods could be overloaded. If the node determines fusion should happen, then the new pipeline it produces is not the original pipeline naively extended with a new node, but instead has a new, fused output node:

impl Plan<U> for Map<T, U, Upstream> {

// Map/map fusion

fn then_map<V>(self: Arc<Self>, f: Fn(U) -> V)

-> Arc<Plan<V>>

{

return Arc::new(Map {

// Fused map function

map_fn: compose(f, self.map_fn),

// Directly attach the fused node to the upstream; the graph size

// doesn't increase

upstream: self.upstream,

});

}

}Data-parallel algorithms

We implemented a suite of generic data-parallel algorithms with varying degrees of difficulty in task decomposition. These algorithms, in turn, form the building blocks of data-parallel programs that the user construct with the dataflow engine.

Task granularity and adaptive schedulingIn our implementation of data-parallel algorithms, we frequently use tree decomposition on tasks. Tree decomposition can split tasks into arbitrarily small chunks, but it is usually desirable to have a coarser granularity of tasks, below which we switch to sequential processing. Otherwise, parallel orchestration overhead will dominate.

Determining the appropriate granularity is an implausible task for us, since the algorithms are generic and receive user-defined functions, which we have no way of knowing the runtime profile of. Instead, we use a heuristic: each task is divided into roughly chunks. This provides some overdecomposition that enables load balancing on workloads that are not extremely skewed, while not so much that parallel orchestration overhead becomes a concern.

Another more sophisticated strategy employed by frameworks like

rayonis adaptive scheduling: a task is divided into a small number of chunks (like ), but when a task is stolen, it is further divided into smaller chunks, since stolen tasks imply some degree of load imbalance that needs to be eased.

Map

Source

src/algorithm/map.rs

The map operation applies a transformation on all elements of the collection independently. This is arguably the easiest algorithm to parallelize. The task decomposition is trivial:

- mapping over one element is accomplished by writing the transformed value to the destination, whose index is already known (it’s the same as the input index);

- mapping over a collection is therefore directly equivalent to mapping over its two halves.

Therefore, we can easily decompose this task in a tree fashion and parallelize over them by join(). This is work-optimal, having work and span (due to the tree decomposition).

Filter

Source

src/algorithm/filter.rs

The filter operation tests all elements of the collection against a predicate and only keeps those that satisfy the predicate. This proved harder to parallelize. Since we do not know beforehand which index each element would be written to, we cannot write them out directly to their destination like for mapping.

The naive approach with tree decomposition, then, would be to write results out to intermediate buffers and then concatenate them. This turns out to have suboptimal asymptotics: given a collection of size , since the decomposition tree has levels, we end up concatenating the elements times. The total work is therefore , which has an extra log factor compared to the work of the sequential filter algorithm.

We eventually chose to implement a three-pass algorithm, which is similar to the prefix-sum scan algorithm used on GPUs that we saw in class, but with some subtle differences. This algorithm, as the name suggests, comprises three passes:

- The first pass involves producing a mask over the collection. The elements that passed the predicate have a mask value of 1, while those that don’t have a mask value of 0. This pass decomposes similar to a mapping operation.

- The second pass involves each worker thread taking a static partition of the mask and performing a sum over that partition. From this we can derive the starting index for each partition by a prefix sum over these partition sums (which is done sequentially since the number of partitions is small).

- Each worker thread can then write elements in its partition to the destination buffer in parallel.

The work of this algorithm is optimally (albeit maybe with a high constant factor due to multiple passes).

Task imbalance and overdecompositionNote that the third pass is susceptible to workload imbalance if the number and size of elements differ greatly across partitions. Our rationale is that the predicates (which are load balanced) usually take up the bulk of the execution time. This might not be the case all of the times.

One thing we can do to rectify this is to overdecompose in the second pass into more partitions than there are threads. Then, threads can dynamically distribute these partitions via

join()similar to the first pass, and the entire algorithm is load-balanced.

Map-filter and fusion

Source

src/plan/map.rs,src/plan/filter.rs

A map-filter operation, as the name suggests, is a combination of the map and the filter operation: it applies a transformation over each element of the collection, but the transformation could return a special “nothing” value to indicate omission of the element. In Rust, this transformation is represented as returning a value of the enum type Option<T>, which is either None or Some(v) for a value v of type T.

The implementation of a map-filter operation is also a variant of the three-pass algorithm described in the last section:

- The first pass involves producing a buffer of the outputs. Each element is transformed and written directly to the corresponding index in this buffer.

- The second pass involves each worker thread taking a static partition of the buffer and performing a count of

Somevalues over that partition. From this we can derive the starting index for each partition by a prefix sum over these partition sums (which is done sequentially since the number of partitions is small). - Each worker thread can then write elements in its partition to the destination buffer in parallel.

The primary reason we included the map-filter operation is fusion. Arbitrarily long chains of maps, filters, and map-filters, can be easily fused into one map-filter operation. In fact, this is exactly the fusion strategy we implemented in nylon.

Fusion and duplicate workRecall we mentioned that

nylonnaturally avoids duplicate work in its execution model. Unfortunately, operator fusion reintroduces duplication into the picture. Imagine a given dataflow graph node A.

- User uses node A as the upstream of operation B, which is fusable with A. A fused output node AB is produced.

- User then uses node A as the upstream of operation C, which is not fusable with A. C is therefore normally chained after A.

In this case, both a fused node AB and a chain A-C exists in the dataflow graph independent of each other, and both will end up performing the work of the (logical) node A.

A potential solution to this is to allow users to introduce pipeline breakers, special nodes that do no work but explicitly act as a barrier to fusion in the dataflow graph.

Reduce-by-key and group-by-key

Source

src/algorithm/reduce_by_key.rs,src/algorithm/group_by_key.rs

A reduce-by-key operation combines all values that share the same key using a user-defined associative operator; a group-by-key operation collects all values that share the same key into collections.

The naive tree decomposition of these operations is to produce partial hash maps for each partition, and then “merge” these hash maps, including combining the values/collections for each key, at each level of the decomposition tree.

This turns out to be work-suboptimal. In the balanced case, the work is ( is the number of keys), which has an extra term compared to the sequential algorithm due to the tree-style merging of hash tables.

We therefore employed a more sophisticated algorithm. The algorithm for reduce-by-key proceeds as follows, and that of group-by-key is analogous:

- Partition the key space. We do this by partitioning over the hash value of the keys; we also overdecompose by a factor of 4. Each worker thread has a thread-local array of hash maps corresponding to the partitions.

- The input is then divided across threads using tree decomposition, and each thread accumulates combined values in their corresponding local hash maps. No merging of hash maps take place in this step.

- The key space partitions are divided across threads using tree decomposition. For each partition, the hash maps for that partition across all threads are merged (values for each key are combined).

- Finally, since these merged hash maps have disjoint key spaces, they can be simply concatenated to form the result.

Operator commutativityThis algorithm is work-optimal but requires a stronger property on the user-supplied combine operator: commutativity. In the case of group-by-key, this means that the grouped collections do not preserve relative element order. This is consistent with the behavior of e.g. Spark.

A way to implement this while preserving order is to statically decompose the input in step 2 instead: each fraction of the input has its own array of hash maps that locally preserves order, and the combination pass in step 3 preserves global order by traversing these fractions in order.

The static decomposition may still be load-balanced: it just requires overdecomposing the input into more fractions than there are threads. This however introduces another problem: the total number of hash maps introduced by step 2 will grow quadratically relative to the overdecomposition factor.

Hash join

Source

src/algorithm/hash_join.rs

A join combines two collections by producing one entry for every pair of entries that share the same join key. Hash join is a join algorithm that involves building a hash map on the values of each key for one collection, and then traversing the other collection, producing entries by looking up each key in the hash map. The first step is known as “build”, and the involved collection is the “build side”; the second step is known as “probe”, and the involved collection is the “probe side”.

Notice how the build step is in fact a group-by-key operation. Therefore, we get to reuse our group-by-key implementation from the last section. Then, the probe step proceeds as follows:

- Each thread has a thread-local buffer for storing joined entries.

- Divide the probe side among threads via tree decomposition. They can look up the hash table in parallel and produce entries into their local buffer.

- Perform a compaction similar to what we described for filtering, to combine these local buffers into the result collection.

Note that this algorithm does not preserve relative ordering. Generally, there is no expectation on any sort of ordering preservation for joins, so we deem this acceptable.

We also optimize by always choosing the smaller collection as the build side. Hash join in general involves the cost of traversal of the two input collections, which is fixed and unavoidable, plus the cost of constructing and probing a hash map. Therefore, it is sensible to reduce the hash map costs by choosing the smaller collection.

Outer joins

There are variants of joins, known as outer joins, that also include unmatched entries. A left outer join includes unmatched entries from the collection on the left side of the join; right outer join is symmetric. A full outer join includes unmatched entries from both sides of the join.

In addition to the regular join (or “inner join”), we implemented the three kinds of outer joins. It is easy to see how outer joins on the probe side would be implemented; we simply include any entries that do not have a corresponding entry on the build side.

Implementing build-side outer join is harder. We attached an atomic flag to each key, which is set to true when the key is first probed. Then, at the end of the join, we traverse the hash map and include entries from keys that do not have the flag set.

This naturally introduces some worries about cache contention. We attempted to reduce cache contention by having key accesses not set the flag blindly, but do an atomic read first and avoid setting the flag if it is already true. This non-atomic test-and-set uses a similar idea to the test-and-test-and-set locks discussed in class, and avoids invalidating the cache line of the flag repeatedly.

Merge sort

Source

src/algorithm/merge_sort.rs

Merge sort is an algorithm that is widely known to parallelize well. We implemented parallel merge sort in nylon, which, as expected, involves a simple tree decomposition:

- Split the input in half.

- Sort the two halves in parallel.

- Merge the two halves into the output buffer.

This naive implementation is already work-optimal. However, it does involve some unnecessary work that slows the algorithm down in practice: each merging requires allocating an output buffer, so there are in total expensive heap allocations.

The optimization lies in realizing that buffers can be reused; as soon as the two halves are merged into the buffer, the memory that stored those halves can now be reused as the new buffer. This is sometimes known as the “ping-pong” optimization as data repeatedly travels between two buffers.

Benchmarking

We implemented some synthetic and realistic benchmarking tasks to see how nylon performs in terms of speedup. These benchmarks are performed on the Intel i9-13900H mobile processor, which has 6 P-cores with SMT and 8 E-cores, i.e. 20 hardware threads in total.

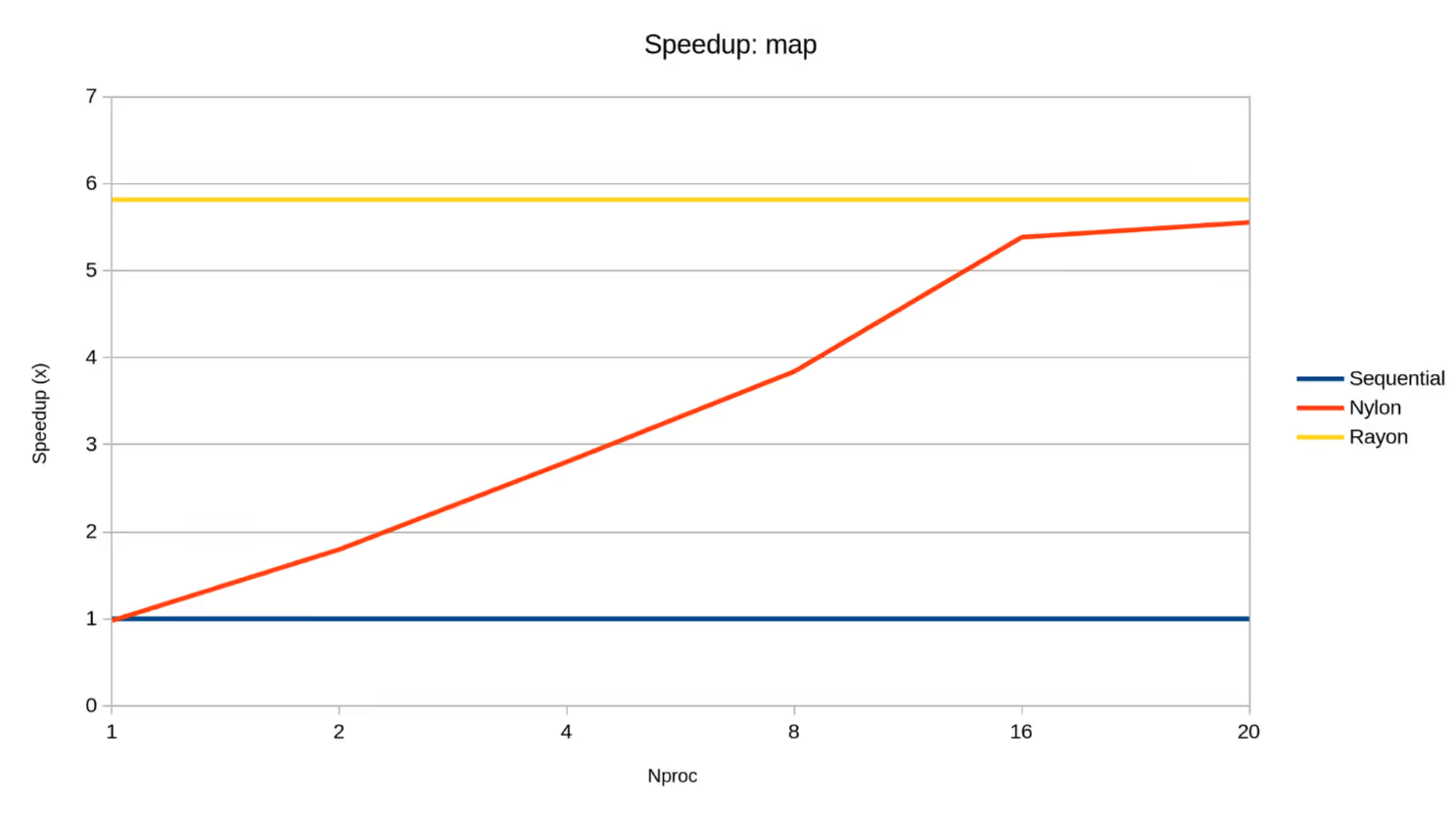

Map synthetic

Source

benches/map.rs

This synthetic task involved mapping over a collection of integers, doing synthetic work — naively computing the n-th Fibonacci number — for each element. The integers are unevenly distributed, so we can gauge our library’s load balancing.

We included rayon’s performance at 20 threads as an aspirational target. Overall, our library generated good speedup, although the speedup did not scale non-linearly.

Apart from the higher orchestration cost that comes with more threads, we suspect that the heterogeneous architecture of the processor we are benchmarking on plays a part. An E-core would not be able to contribute the same compute as a P-core, and an extra SMT thread on the P-core would contribute even less, as we saw in class. This would lead to diminishing returns on highly parallel workloads as we scale the thread count.

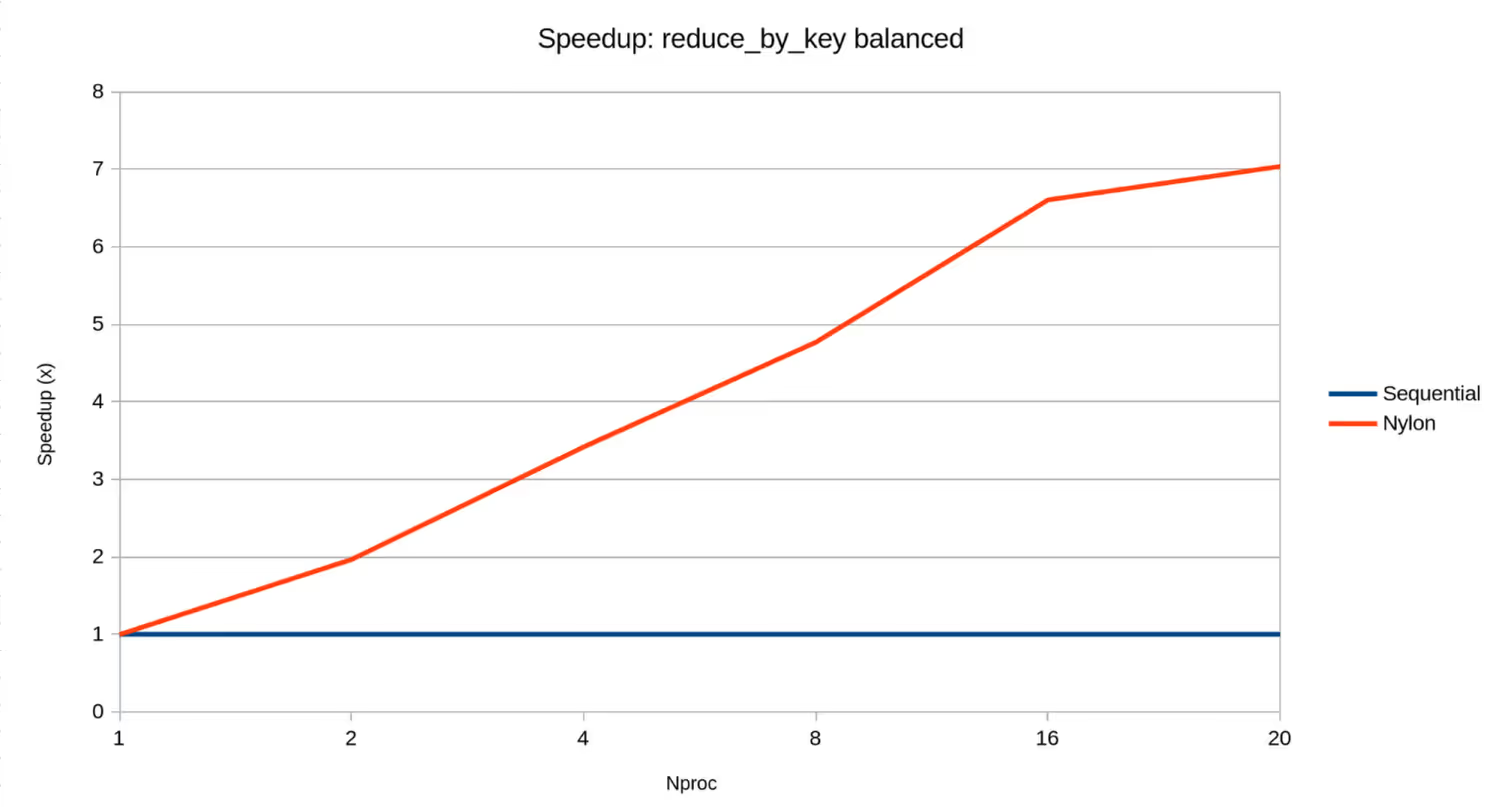

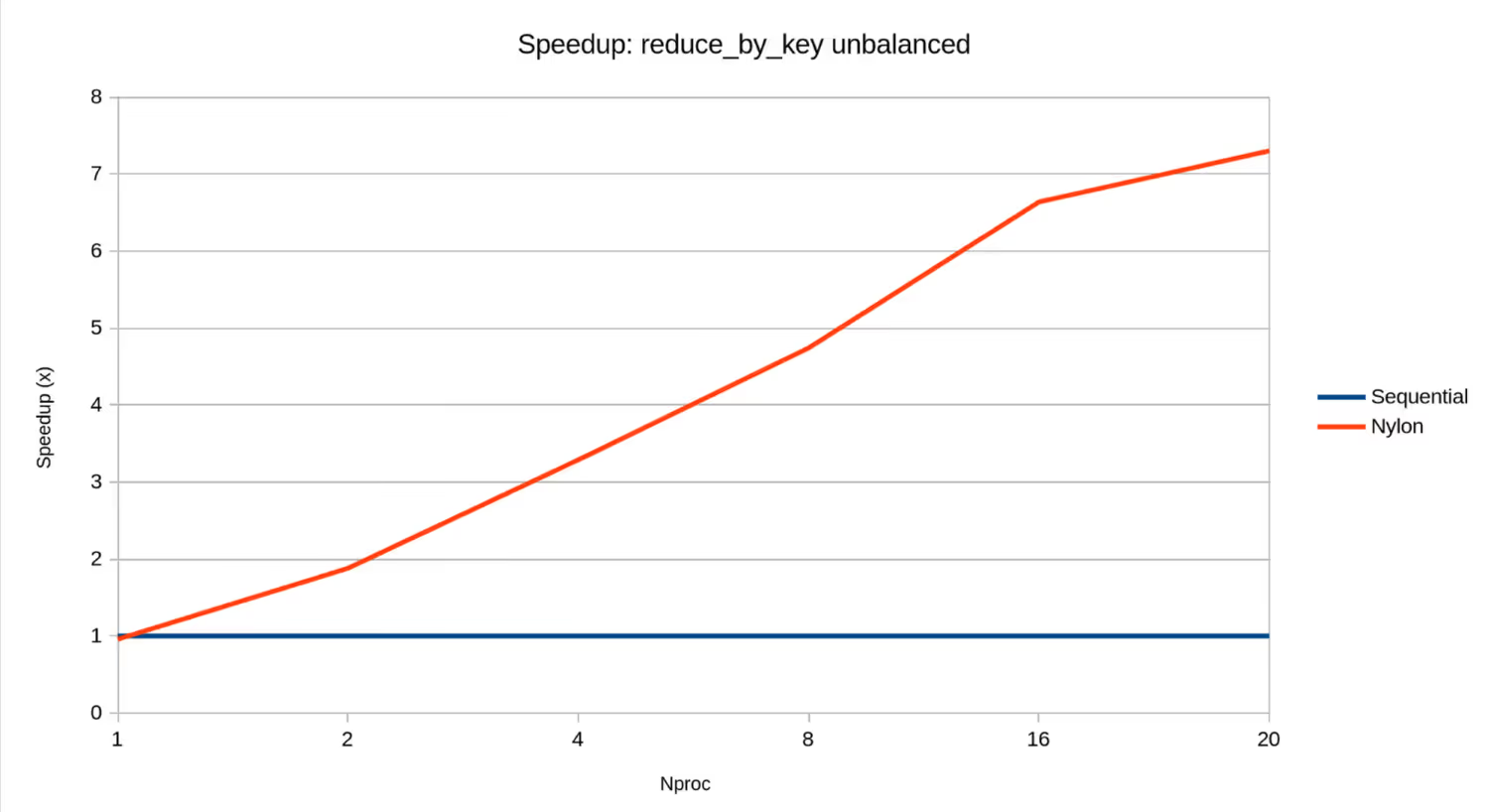

Reduce-by-key synthetic

Source

benches/reduce_by_key.rs

This synthetic task involved reducing by key over a collection of entries (k, v) where k and v are both integers, doing synthetic work — computing gcd(gcd(v1, BIG_PRIME), gcd(v2, BIG_PRIME)) — as the combination operation.

There are two variants of this tasks: the balanced variant includes 1000 keys each with 100 values. The imbalanced variant includes 100 keys with 1000 values, and 1000 keys with 10 values.

Overall, our library performs similarly across the balanced and imbalanced variants, producing good speedup. This further demonstrates that our library is capable of load-balancing uneven work.

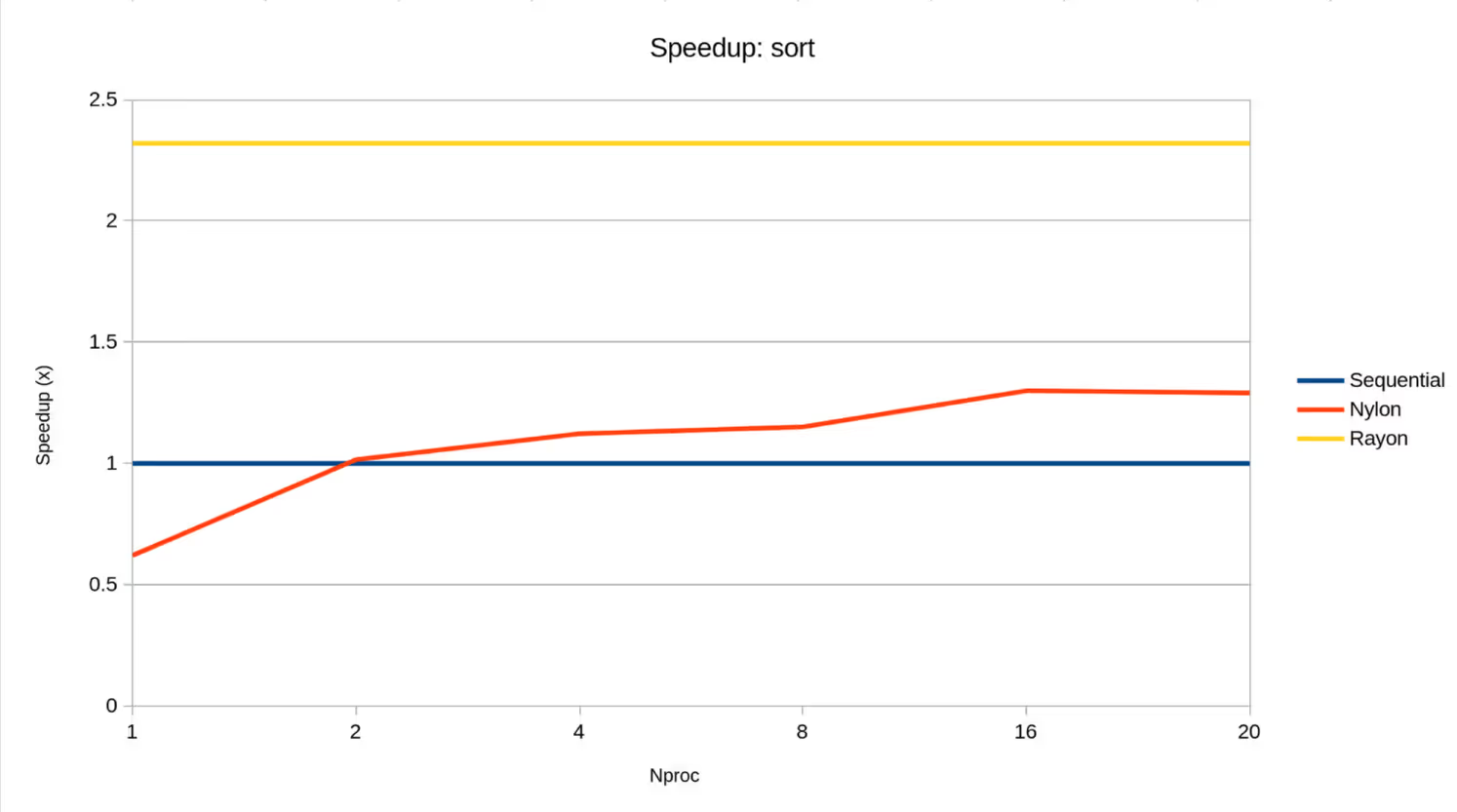

Sort synthetic

Source

benches/sort.rs

This synthetic task sorts a large collection of integers .

We included rayon’s performance at 20 threads as an aspirational target. Overall, our implementation performed poorly on this task compared to rayon; we think this is because our merge sort implementation is still not well-optimized enough.

In general, also, the speedup of both our library and rayon was not ideal: rayon achieved the highest speedup of 2.5x at 20 threads. We think this suggests that this task is bound by a memory bandwidth bottleneck.

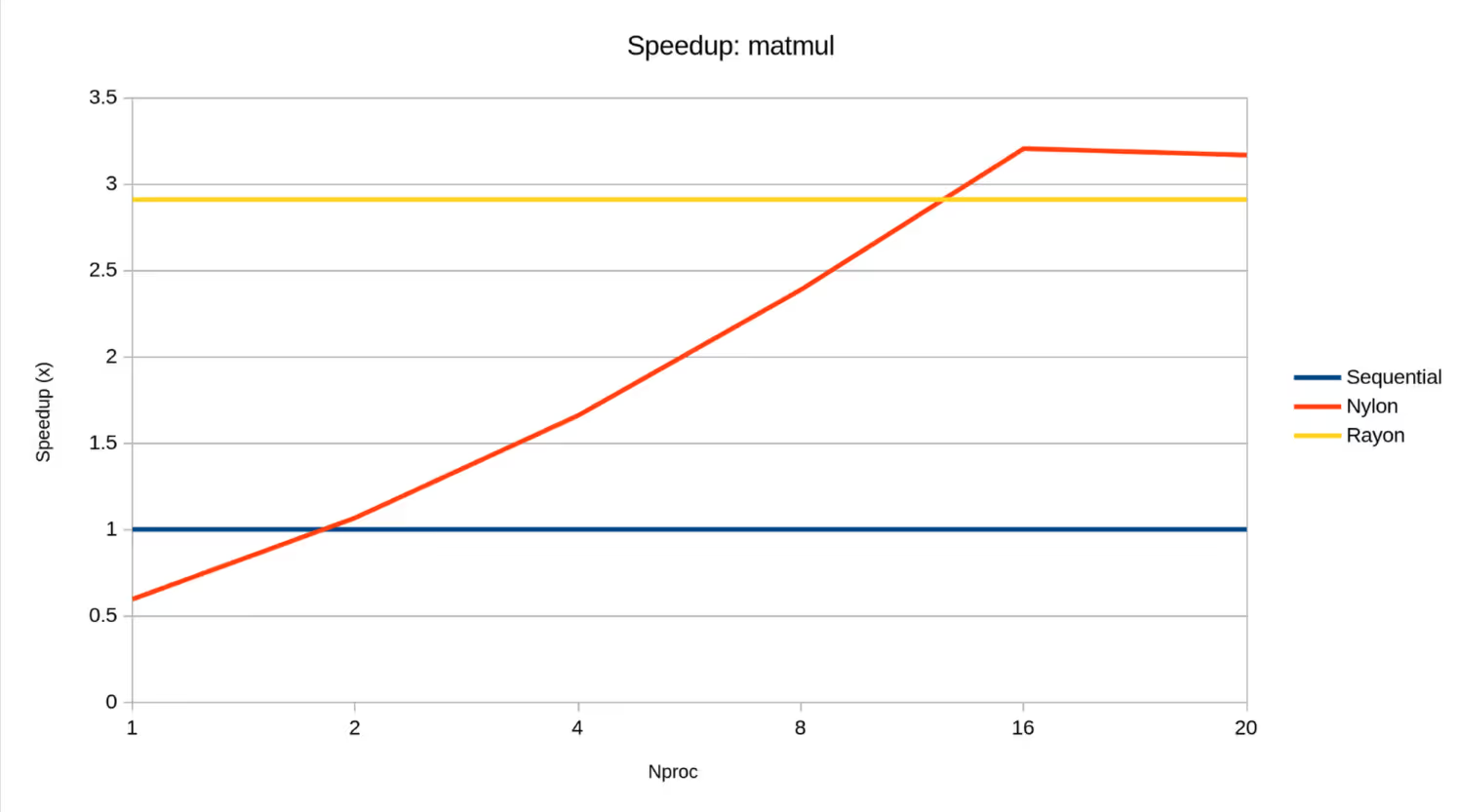

Matrix block multiplication

Source

benches/matmul.rs

This realistic task performs block matrix multiplication over matrices; block size is . It aims to gauge the performance of numeric applications.

We included rayon’s performance at 20 threads as an aspirational target. We were surprised to find that our speedup was in fact better than rayon. Overall, speedup on this task is present but not impressive; it topped out at around 3.2x at 16 threads. We suspect that memory bandwidth saturation, as well as suboptimal cache efficiency, are the main issues here.

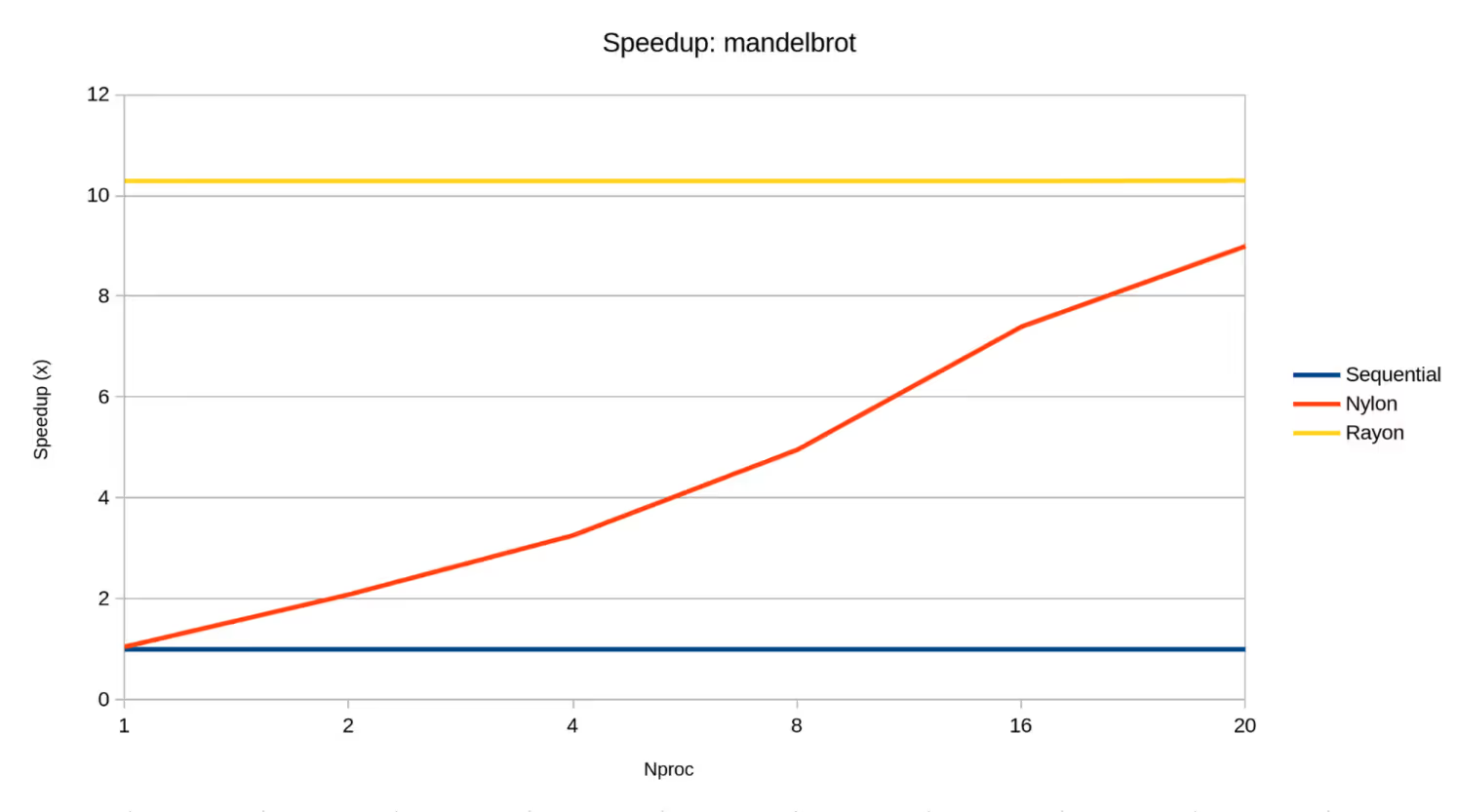

Mandelbrot set

Source

benches/mandelbrot.rs

This realistic task computes the Mandelbrot set as a image with 10-bit depth. It aims to gauge the performance on image processing tasks, Monte Carlo simulations, and tasks with uneven work distribution.

We included rayon’s performance at 20 threads as an aspirational target. Our performance on this task contrasts with the last: here, we underperformed rayon. One factor is obviously that our dataflow engine is more general than rayon, so more overhead is involved.

Another thing to note is that while matrix multiplication is a highly uniform workload, Mandelbrot set calculation is highly irregular. This could therefore be pointing at our engine being more optimized for balanced workloads, and less so for imbalanced ones. This makes intuitive sense, since rayon uses a more sophisticated adaptive work allocation scheme.

Conclusion

This project spanned many domains within parallel computing: dynamic work scheduling, efficient parallel algorithms, and implementing dataflow programming models.

Obviously, our implementation is primarily for the sake of learning and cannot match the scale or performance of industrial systems and frameworks. Nevertheless, we regard the learning that we gained from this process to be invaluable in itself. Seeing our framework produce tangible speedups over sequential programs while also enabling high-level dataflow programming felt deeply satisfying; realizing the limitations and tradeoffs involved with both using and implementing such a high-level programming model was similarly interesting.

References

rayon.rayon-rscontributors.

rayonwas used as a stand-in for a functional work-stealing scheduler when we developed our scheduler and parallel algorithms in parallel. We also referencedrayonwhen making design decisions for our scheduler.

crossbeam.crossbeam-rscontributors.

We used

crossbeamfor some concurrency primitives in our project, mainly the lock-free Chase-Lev queue for work stealing, and the Parker abstraction for thread sleeping.

- Apache Spark. The Apache Software Foundation.

- Apache Beam. The Apache Software Foundation.

We referenced Apache Spark and Beam in API design.

- Apache Flink. The Apache Software Foundation.

We briefly surveyed Apache Flink when considering pipeline parallelism before eventually deciding against it.

- OpenMP. OpenMP Architecture Review Board.

Although not directly linked to our project’s implementation, we frequently framed OpenMP as a contrasting alternative approach when considering design decisions.